Evidence that inspires our work

We're committed to robust impact evaluation of our work, rooted in the strongest research evidence

Share this page

Why do we support young struggling readers who face disadvantage?

Struggling readers need more reading support than classroom teaching alone (Lavan & Talcott, 2020).

Children who face disadvantage have fewer opportunities to develop reading skills compared to their peers (Carroll et al., 2020; National Literacy Trust, 2023).

1 in 8 children (12%) aged 5 - 8 in receipt of free school meals don’t own a single book compared to 1 in 13 (8%) of their peers (National Literacy Trust, 2024).

33% of five year olds in the most deprived areas compared to 28% in the least deprived areas do not reach the expected communication, language and literacy skills (Pro Bono Economics, 2024).

Primary school children who face disadvantage lag behind their peers in reading attainment by six to seven months’ progress (Education Endowment Foundation, 2024).

38% of 11 year olds in England from disadvantaged backgrounds compared to 20% from non-disadvantaged backgrounds leave primary school unable to read to the expected standard (Department for Education, 2024)

It is crucial to support children facing disadvantage early on in their reading journey (Pro Bono Economics, 2024) and engaging children at a young age in reading can mitigate against disadvantage (Torppa et al., 2020).

There is a crisis of reading enjoyment among children in general (Clark et al., 2024) but reading enjoyment is even lower in children from disadvantaged backgrounds compared to non-disadvantaged backgrounds (Clark et al., 2023).

What are the benefits of reading/literacy?

Children who read are more likely to experience a variety of benefits, such as:

Overcoming disadvantage caused by inequalities (Sullivan & Brown, 2013; Sammons et al., 2015)

Better wellbeing (Clark & Teravainen-Goff, 2018)

Increased life expectancy (Gilbert et al., 2018).

Better educational attainment (Sullivan & Brown, 2015; National Literacy Trust/British Land, 2021)

Increased employment opportunities/future income/lifetime earnings (National Literacy Trust/British Land, 2021)

Children with better ‘life skills’ such as confidence, motivation and communication skills (verbal or oracy skills) are more likely to have improved life chances (The Sutton Trust, 2024).

Why is it important to develop positive attitudes towards reading in children?

Reading attitudes such as reading confidence and reading enjoyment influence reading attainment and vice versa (Clark et al., 2024; Cremin, 2023; McGeown et al., 2015).

Children’s attitudes towards reading tend to become less positive with age and therefore it is especially important to foster and protect positive attitudes towards reading from a young age (McGeown et al., 2015).

Children who enjoy reading and who read for pleasure reap cognitive, social and benefits to wellbeing (Cremin, 2023; Sun et al., 2024).

Reading for pleasure is more important in children’s development and for their life chances than their socio-economic background and parental education (Sullivan & Brown, 2013).

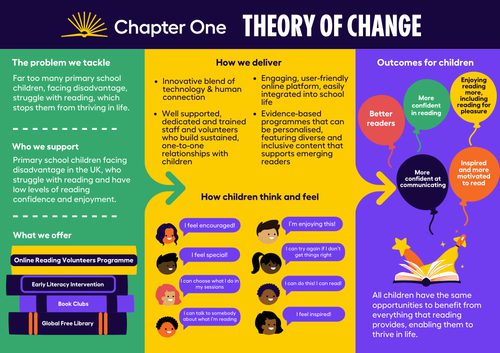

How does Chapter One’s delivery model support children’s reading/literacy?

Integrating technology with human connection may lead to greater impact on children’s reading than humans alone (Chambers et al., 2008; Cortes et al., 2025).

One-to-one consistent and sustained support is effective for children who struggle with reading/literacy (Cortes et al., 2025; Education Endowment Foundation, 2020; Neitzel et al., 2022; Slavin et al., 2011).

Self-determination theory highlights three fundamental human needs: autonomy (need to feel in control of one’s own behaviours), competence (need to gain mastery of tasks) and relatedness (need to experience a sense of belonging to other people) (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Supporting these three aspects in children’s reading helps to develop children’s reading motivation and volitional reading (Cremin et al., 2023).

Successful reading interventions incorporate the notion of reading as a shared social experience (Lee & Szczerbinski, 2019; Cremin et al., 2023), with sufficient time for adults/volunteers and children to build trusting relationships (Cremin et al., 2023).

Adults who support children to read can become role models who positively influence children’s engagement in volitional reading (Cremin et al., 2023; Lee & Szczerbinski, 2019) and positive social influence can support children to become avid readers (Merga, 2017).

Children are more likely to become independent readers when they read with multiple people – ‘reading influencers’ (BookTrust, 2023).

It is important for children to have access to inclusive and diverse reading materials (CLPE, 2022; Picton & Clark, 2022), whereby children ‘see themselves’ within books but equally learn about the lives of others (Picton & Clark, 2022).

Children need to develop effective verbal communication and active listening skills to be able to thrive in the rapidly changing digital-first world and workplace (National Literacy Trust, 2025)

BookTrust. (2023). The role of multiple ‘reading influencers’ in supporting children’s reading journeys.

Carroll, C., Hurry, J., Grima, G., Hooper, A., Dunn, K., & Ahtaridou, E. (2020). Evaluation of Bug Club: a randomised control trial of a whole school primary aged reading programme. The Curriculum Journal, 31 (4), 605-625.

Chambers, B., Abrami, P., Tucker, B., Slavin, R. E., Madden, N. A., Cheung, A., & Gifford, R. (2008). Computer-assisted tutoring in Success for All: Reading outcomes for first graders. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 1 (2), 120-137.

Clark, C., Picton, I., Cole, A., & Oram, N. (2024). Children and Young People’s Reading in 2024. London: National Literacy Trust

Clark, C., Picton, I. & Galway, M. (2023). Children and young people’s reading in 2023. London: National Literacy Trust.

Clark, C., & Teravainen-Goff, A. (2018). Mental Wellbeing, Reading and Writing: How Children and Young People's Mental Wellbeing Is Related to Their Reading and Writing Experiences. National Literacy Trust Research Report. National Literacy Trust.

Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE). (2022). Reflecting Realities. Survey of Ethnic Representation within UK children’s literature 2017 - 2021.

Cortes, K. E., Kortecamp, K., Loeb, S., & Robinson, C. D. (2025). A scalable approach to high-impact tutoring for young readers. Learning and Instruction, 95, 102021.

Cremin, T. (2023). Reading for pleasure: Recent research insights. School Libraries in View (SLIV)(47) pp. 6–12.

Cremin, T.,Hendry, H., Chamberlain, L., & Hulston, S. (2023). Approaches to Reading and Writing for Pleasure: An Executive Summary of the Research. The Mercers' Company, London.

Education Endowment Foundation. (2020). Improving literacy in Key Stage 1. Guidance Report.

Education Endowment Foundation. (2024). Impact of Key Stage 1 school closures on later attainment and social skills (a longitudinal study).

Gilbert, L., Teravainen, A., Clark, C., & Shaw, S. (2018). Literacy and life expectancy: An evidence review exploring the link between literacy and life expectancy in England through health and socioeconomic factors. London: National Literacy Trust.

Lavan, G., & Talcott, J. (2020). Brooks’s what works for literacy difficulties?. The Effectiveness of Intervention Schemes.

Lee, L., & Szczerbinski, M. (2021). Paired Reading as a method of reading intervention in Irish primary schools: an evaluation. Irish Educational Studies, 40(3), 589-610.

McGeown, S. P., Johnston, R. S., Walker, J., Howatson, K., Stockburn, A., & Dufton, P. (2015). The relationship between young children’s enjoyment of learning to read, reading attitudes, confidence and attainment. Educational Research, 57(4), 389–402.

Merga, M. (2017). Becoming a Reader: Significant Social Influences on Avid Book Readers. School library research, Vol. 20.

National Literacy Trust/British Land. (2021). The power of reading for pleasure. Boosting children’s life chances. London: National Literacy Trust

National Literacy Trust. (2023). Children and young people’s access to books and educational devices at home during the cost-of-living crisis. A survey of over 3000 parents and carers in 2023. London: National Literacy Trust

National Literacy Trust. (2025). The future of literacy: The human advantage. How literacy skills drive success in a digital-first workplace.

Neitzel, A. J., Lake, C., Pellegrini, M., & Slavin, R. E. (2022). A synthesis of quantitative research on programs for struggling readers in elementary schools. Reading Research Quarterly, 57 (1), 149-179.

Picton, I. & Clark, C. (2022). Diversity and children and young people’s reading in 2022. London: National Literacy Trust.

Picton, I., Clark, C., & Oram, N. (2024). Children and Young People's Book Ownership in 2024. National Literacy Trust.

Pro Bono Economics. (2024). Early literacy matters: Economic impact and regional disparities in England.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55 (1), 68.

Sammons, P., Toth, K., & Sylva, K. (2015). Subject to Background: What promotes better achievement by bright but disadvantaged students? Sutton Trust.

Slavin, R. E., Lake, C., Davis, S., & Madden, N. A. (2011). Effective programs for struggling readers: A best-evidence synthesis. Educational Research Review, 6 (1), 1-26.

Sullivan, A., & Brown, M. (2013). Social inequalities in cognitive scores at age 16: The role of reading. CLS Working Papers, 2013(13/10).

Sullivan, A., & Brown, M. (2015). Reading for pleasure and progress in vocabulary and mathematics. British Educational Research Journal, 41 (6), 971 - 991.

Sun, Y. J., Sahakian, B. J., Langley, C., Yang, A., Jiang, Y., Kang, J., ... & Feng, J. (2024). Early-initiated childhood reading for pleasure: associations with better cognitive performance, mental well-being and brain structure in young adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 54(2), 359-373.

The Sutton Trust. (2024). Life Lessons 2024. The development of oracy and other life skills in school.

Torppa, M., Niemi, P., Vasalampi, K., Lerkkanen, M. K., Tolvanen, A., & Poikkeus, A. M. (2020). Leisure reading (but not any kind) and reading comprehension support each other—A longitudinal study across grades 1 and 9. Child development, 91 (3), 876-900.

It all starts with literacy.